Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics are used to quantitatively describe the main characteristics of the data. They provide meaningful summaries computed over different observations or data records collected in a study. These summaries typically form the basis of the initial data exploration as part of a more extensive statistical analysis. Such a quantitative analysis assumes that every variable (also known as, attribute, feature, or column) in the data has a specific level of measurement [Stevens1946].

The measurement level of a variable, often called as variable type, can either be scale or categorical. A scale variable represents the data measured on an interval scale or ratio scale. Examples of scale variables include ‘Height’, ‘Weight’, ‘Salary’, and ‘Temperature’. Scale variables are also referred to as quantitative or continuous variables. In contrast, a categorical variable has a fixed limited number of distinct values or categories. Examples of categorical variables include ‘Gender’, ‘Region’, ‘Hair color’, ‘Zipcode’, and ‘Level of Satisfaction’. Categorical variables can further be classified into two types, nominal and ordinal, depending on whether the categories in the variable can be ordered via an intrinsic ranking. For example, there is no meaningful ranking among distinct values in ‘Hair color’ variable, while the categories in ‘Level of Satisfaction’ can be ranked from highly dissatisfied to highly satisfied.

The input dataset for descriptive statistics is provided in the form of a matrix, whose rows are the records (data points) and whose columns are the features (i.e. variables). Some scripts allow this matrix to be vertically split into two or three matrices. Descriptive statistics are computed over the specified features (columns) in the matrix. Which statistics are computed depends on the types of the features. It is important to keep in mind the following caveats and restrictions:

-

Given a finite set of data records, i.e. a sample, we take their feature values and compute their sample statistics. These statistics will vary from sample to sample even if the underlying distribution of feature values remains the same. Sample statistics are accurate for the given sample only. If the goal is to estimate the distribution statistics that are parameters of the (hypothesized) underlying distribution of the features, the corresponding sample statistics may sometimes be used as approximations, but their accuracy will vary.

-

In particular, the accuracy of the estimated distribution statistics will be low if the number of values in the sample is small. That is, for small samples, the computed statistics may depend on the randomness of the individual sample values more than on the underlying distribution of the features.

-

The accuracy will also be low if the sample records cannot be assumed mutually independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), that is, sampled at random from the same underlying distribution. In practice, feature values in one record often depend on other features and other records, including unknown ones.

-

Most of the computed statistics will have low estimation accuracy in the presence of extreme values (outliers) or if the underlying distribution has heavy tails, for example obeys a power law. However, a few of the computed statistics, such as the median and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, are robust to outliers.

-

Some sample statistics are reported with their sample standard errors in an attempt to quantify their accuracy as distribution parameter estimators. But these sample standard errors, in turn, only estimate the underlying distribution’s standard errors and will have low accuracy for small or samples, outliers in samples, or heavy-tailed distributions.

-

We assume that the quantitative (scale) feature columns do not contain missing values, infinite values,

NaNs, or coded non-numeric values, unless otherwise specified. We assume that each categorical feature column contains positive integers from 1 to the number of categories; for ordinal features, the natural order on the integers should coincide with the order on the categories.

Univariate Statistics

Univariate statistics are the simplest form of descriptive statistics

in data analysis. They are used to quantitatively describe the main

characteristics of each feature in the data. For a given dataset matrix,

script Univar-Stats.dml computes certain univariate

statistics for each feature column in the matrix. The feature type

governs the exact set of statistics computed for that feature. For

example, the statistic mean can only be computed on a quantitative

(scale) feature like ‘Height’ and ‘Temperature’. It does not make sense

to compute the mean of a categorical attribute like ‘Hair Color’.

Table 1

The output matrix of Univar-Stats.dml has one row per

each univariate statistic and one column per input feature. This table

lists the meaning of each row. Signs “+” show applicability to scale

or/and to categorical features.

| Row | Name of Statistic | Scale | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Minimum | + | |

| 2 | Maximum | + | |

| 3 | Range | + | |

| 4 | Mean | + | |

| 5 | Variance | + | |

| 6 | Standard deviation | + | |

| 7 | Standard error of mean | + | |

| 8 | Coefficient of variation | + | |

| 9 | Skewness | + | |

| 10 | Kurtosis | + | |

| 11 | Standard error of skewness | + | |

| 12 | Standard error of kurtosis | + | |

| 13 | Median | + | |

| 14 | Interquartile mean | + | |

| 15 | Number of categories | + | |

| 16 | Mode | + | |

| 17 | Number of modes | + |

Univariate Statistics Details

Given an input matrix X, this script computes the set of all relevant

univariate statistics for each feature column X[,i] in X. The list

of statistics to be computed depends on the type, or measurement

level, of each column. The command-line argument points to a vector

containing the types of all columns. The types must be provided as per

the following convention: 1 = scale, 2 = nominal,

3 = ordinal.

Below we list all univariate statistics computed by script

Univar-Stats.dml. The statistics are collected by

relevance into several groups, namely: central tendency, dispersion,

shape, and categorical measures. The first three groups contain

statistics computed for a quantitative (also known as: numerical, scale,

or continuous) feature; the last group contains the statistics for a

categorical (either nominal or ordinal) feature.

Let $n$ be the number of data records (rows) with feature values. In

what follows we fix a column index idx and consider sample statistics

of feature column X[$\,$,$\,$idx]. Let

$v = (v_1, v_2, \ldots, v_n)$ be the values of X[$\,$,$\,$idx] in

their original unsorted order:

$v_i = \texttt{X[}i\texttt{,}\,\texttt{idx]}$. Let

$v^s = (v^s_1, v^s_2, \ldots, v^s_n)$ be the same values in the sorted

order, preserving duplicates: $v^s_1 \leq v^s_2 \leq \ldots \leq v^s_n$.

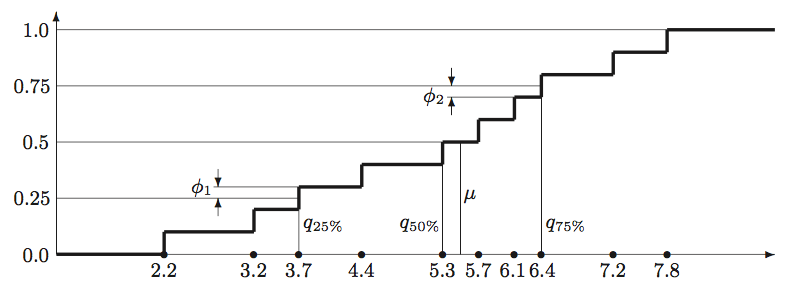

Figure 1

The computation of quartiles, median, and interquartile mean from the

empirical distribution function of the 10-point

sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8}. Each vertical step in

the graph has height $1{/}n = 0.1$. Values $q_{25\%}$, $q_{50\%}$, and

$q_{75\%}$ denote the $1^{\textrm{st}}$, $2^{\textrm{nd}}$, and

$3^{\textrm{rd}}$ quartiles correspondingly;

value $\mu$ denotes the median. Values $\phi_1$ and $\phi_2$ show the partial contribution

of border points (quartiles) $v_3=3.7$ and $v_8=6.4$ into the interquartile mean.

Central Tendency Measures

Sample statistics that describe the location of the quantitative (scale) feature distribution, represent it with a single value.

Mean (output row 4): The arithmetic average over a sample of a quantitative feature. Computed as the ratio between the sum of values and the number of values: $\left(\sum_{i=1}^n v_i\right)!/n$. Example: the mean of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals 5.2.

Note that the mean is significantly affected by extreme values in the sample and may be misleading as a central tendency measure if the feature varies on exponential scale. For example, the mean of {0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0, 100.0} is 22.222, greater than all the sample values except the largest.

Median (output row 13): The “middle” value that separates the higher half of the sample values (in a sorted order) from the lower half. To compute the median, we sort the sample in the increasing order, preserving duplicates: $v^s_1 \leq v^s_2 \leq \ldots \leq v^s_n$. If $n$ is odd, the median equals $v^s_i$ where $i = (n\,{+}\,1)\,{/}\,2$, same as the $50^{\textrm{th}}$ percentile of the sample. If $n$ is even, there are two “middle” values $v^s_{n/2}$ and $v^s_{n/2\,+\,1}$, so we compute the median as the mean of these two values. (For even $n$ we compute the $50^{\textrm{th}}$ percentile as $v^s_{n/2}$, not as the median.) Example: the median of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals $(5.3\,{+}\,5.7)\,{/}\,2$ ${=}$ 5.5, see Figure 1.

Unlike the mean, the median is not sensitive to extreme values in the sample, i.e. it is robust to outliers. It works better as a measure of central tendency for heavy-tailed distributions and features that vary on exponential scale. However, the median is sensitive to small sample size.

Interquartile mean (output row 14): For a sample of a quantitative feature, this is the mean of the values greater than or equal to the $1^{\textrm{st}}$ quartile and less than or equal the $3^{\textrm{rd}}$ quartile. In other words, it is a “truncated mean” where the lowest 25$\%$ and the highest 25$\%$ of the sorted values are omitted in its computation. The two “border values”, i.e. the $1^{\textrm{st}}$ and the $3^{\textrm{rd}}$ quartiles themselves, contribute to this mean only partially. This measure is occasionally used as the “robust” version of the mean that is less sensitive to the extreme values.*

To compute the measure, we sort the sample in the increasing order, preserving duplicates: $v^s_1 \leq v^s_2 \leq \ldots \leq v^s_n$. We set $j = \lceil n{/}4 \rceil$ for the $1^{\textrm{st}}$ quartile index and $k = \lceil 3n{/}4 \rceil$ for the $3^{\textrm{rd}}$ quartile index, then compute the following weighted mean:

\[\frac{1}{3{/}4 - 1{/}4} \left[ \left(\frac{j}{n} - \frac{1}{4}\right) v^s_j \,\,+ \sum_{j<i<k} \left(\frac{i}{n} - \frac{i\,{-}\,1}{n}\right) v^s_i \,\,+\,\, \left(\frac{3}{4} - \frac{k\,{-}\,1}{n}\right) v^s_k\right]\]In other words, all sample values between the $1^{\textrm{st}}$ and the $3^{\textrm{rd}}$ quartile enter the sum with weights $2{/}n$, times their number of duplicates, while the two quartiles themselves enter the sum with reduced weights. The weights are proportional to the vertical steps in the empirical distribution function of the sample, see Figure 1 for an illustration. Example: the interquartile mean of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals the sum $0.1 (3.7\,{+}\,6.4) + 0.2 (4.4\,{+}\,5.3\,{+}\,5.7\,{+}\,6.1)$, which equals 5.31.

Dispersion Measures

Statistics that describe the amount of variation or spread in a quantitative (scale) data feature.

Variance (output row 5): A measure of dispersion, or spread-out, of sample values around their mean, expressed in units that are the square of those of the feature itself. Computed as the sum of squared differences between the values in the sample and their mean, divided by one less than the number of values: $\sum_{i=1}^n (v_i - \bar{v})^2\,/\,(n\,{-}\,1)$ where $\bar{v}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^n v_i\right)/n$. Example: the variance of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals 3.24. Note that at least two values ($n\geq 2$) are required to avoid division by zero. Sample variance is sensitive to outliers, even more than the mean.

Standard deviation (output row 6): A measure of dispersion around the mean, the square root of variance. Computed by taking the square root of the sample variance; see Variance above on computing the variance. Example: the standard deviation of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals 1.8. At least two values are required to avoid division by zero. Note that standard deviation is sensitive to outliers.

Standard deviation is used in conjunction with the mean to determine an interval containing a given percentage of the feature values, assuming the normal distribution. In a large sample from a normal distribution, around 68% of the cases fall within one standard deviation and around 95% of cases fall within two standard deviations of the mean. For example, if the mean age is 45 with a standard deviation of 10, around 95% of the cases would be between 25 and 65 in a normal distribution.

Coefficient of variation (output row 8): The ratio of the standard deviation to the mean, i.e. the relative standard deviation, of a quantitative feature sample. Computed by dividing the sample standard deviation by the sample mean, see above for their computation details. Example: the coefficient of variation for sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals 1.8$\,{/}\,$5.2 ${\approx}$ 0.346.

This metric is used primarily with non-negative features such as

financial or population data. It is sensitive to outliers. Note: zero

mean causes division by zero, returning infinity or NaN. At least two

values (records) are required to compute the standard deviation.

Minimum (output row 1): The smallest value of a quantitative sample, computed as $\min v = v^s_1$. Example: the minimum of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals 2.2.

Maximum (output row 2): The largest value of a quantitative sample, computed as $\max v = v^s_n$. Example: the maximum of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals 7.8.

Range (output row 3): The difference between the largest and the smallest value of a quantitative sample, computed as $\max v - \min v = v^s_n - v^s_1$. It provides information about the overall spread of the sample values. Example: the range of sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} equals 7.8$\,{-}\,$2.2 ${=}$ 5.6.

Standard error of the mean (output row 7): A measure of how much the value of the sample mean may vary from sample to sample taken from the same (hypothesized) distribution of the feature. It helps to roughly bound the distribution mean, i.e.the limit of the sample mean as the sample size tends to infinity. Under certain assumptions (e.g. normality and large sample), the difference between the distribution mean and the sample mean is unlikely to exceed 2 standard errors.

The measure is computed by dividing the sample standard deviation by the square root of the number of values $n$; see standard deviation for its computation details. Ensure $n\,{\geq}\,2$ to avoid division by 0. Example: for sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} with the mean of 5.2 the standard error of the mean equals 1.8$\,{/}\sqrt{10}$ ${\approx}$ 0.569.

Note that the standard error itself is subject to sample randomness. Its accuracy as an error estimator may be low if the sample size is small or non-i.i.d., if there are outliers, or if the distribution has heavy tails.

Shape Measures

Statistics that describe the shape and symmetry of the quantitative (scale) feature distribution estimated from a sample of its values.

Skewness (output row 9): It measures how symmetrically the values of a feature are spread out around the mean. A significant positive skewness implies a longer (or fatter) right tail, i.e. feature values tend to lie farther away from the mean on the right side. A significant negative skewness implies a longer (or fatter) left tail. The normal distribution is symmetric and has a skewness value of 0; however, its sample skewness is likely to be nonzero, just close to zero. As a guideline, a skewness value more than twice its standard error is taken to indicate a departure from symmetry.

Skewness is computed as the $3^{\textrm{rd}}$ central moment divided by the cube of the standard deviation. We estimate the $3^{\textrm{rd}}$ central moment as the sum of cubed differences between the values in the feature column and their sample mean, divided by the number of values: $\sum_{i=1}^n (v_i - \bar{v})^3 / n$ where $\bar{v}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^n v_i\right)/n$. The standard deviation is computed as described above in standard deviation. To avoid division by 0, at least two different sample values are required. Example: for sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} with the mean of 5.2 and the standard deviation of 1.8 skewness is estimated as $-1.0728\,{/}\,1.8^3 \approx -0.184$. Note: skewness is sensitive to outliers.

Standard error in skewness (output row 11): A measure of how much the sample skewness may vary from sample to sample, assuming that the feature is normally distributed, which makes its distribution skewness equal 0. Given the number $n$ of sample values, the standard error is computed as

\[\sqrt{\frac{6n\,(n-1)}{(n-2)(n+1)(n+3)}}\]This measure can tell us, for example:

- If the sample skewness lands within two standard errors from 0, its positive or negative sign is non-significant, may just be accidental.

- If the sample skewness lands outside this interval, the feature is unlikely to be normally distributed.

At least 3 values ($n\geq 3$) are required to avoid arithmetic failure. Note that the standard error is inaccurate if the feature distribution is far from normal or if the number of samples is small.

Kurtosis (output row 10): As a distribution parameter, kurtosis is a measure of the extent to which feature values cluster around a central point. In other words, it quantifies “peakedness” of the distribution: how tall and sharp the central peak is relative to a standard bell curve.

Positive kurtosis (leptokurtic distribution) indicates that, relative to a normal distribution:

- Observations cluster more about the center (peak-shaped)

- The tails are thinner at non-extreme values

- The tails are thicker at extreme values

Negative kurtosis (platykurtic distribution) indicates that, relative to a normal distribution:

- Observations cluster less about the center (box-shaped)

- The tails are thicker at non-extreme values

- The tails are thinner at extreme values

Kurtosis of a normal distribution is zero; however, the sample kurtosis (computed here) is likely to deviate from zero.

Sample kurtosis is computed as the $4^{\textrm{th}}$ central moment divided by the $4^{\textrm{th}}$ power of the standard deviation, minus 3. We estimate the $4^{\textrm{th}}$ central moment as the sum of the $4^{\textrm{th}}$ powers of differences between the values in the feature column and their sample mean, divided by the number of values: $\sum_{i=1}^n (v_i - \bar{v})^4 / n$ where $\bar{v}=\left(\sum_{i=1}^n v_i\right)/n$. The standard deviation is computed as described above, see standard deviation.

Note that kurtosis is sensitive to outliers, and requires at least two different sample values. Example: for sample {2.2, 3.2, 3.7, 4.4, 5.3, 5.7, 6.1, 6.4, 7.2, 7.8} with the mean of 5.2 and the standard deviation of 1.8, sample kurtosis equals $16.6962\,{/}\,1.8^4 - 3 \approx -1.41$.

Standard error in kurtosis (output row 12): A measure of how much the sample kurtosis may vary from sample to sample, assuming that the feature is normally distributed, which makes its distribution kurtosis equal 0. Given the number $n$ of sample values, the standard error is computed as

\[\sqrt{\frac{24n\,(n-1)^2}{(n-3)(n-2)(n+3)(n+5)}}\]This measure can tell us, for example:

- If the sample kurtosis lands within two standard errors from 0, its positive or negative sign is non-significant, may just be accidental.

- If the sample kurtosis lands outside this interval, the feature is unlikely to be normally distributed.

At least 4 values ($n\geq 4$) are required to avoid arithmetic failure. Note that the standard error is inaccurate if the feature distribution is far from normal or if the number of samples is small.

Categorical Measures

Statistics that describe the sample of a categorical feature, either nominal or ordinal. We represent all categories by integers from 1 to the number of categories; we call these integers category IDs.

Number of categories (output row 15): The maximum category ID that occurs in the sample. Note that some categories with IDs smaller than this maximum ID may have no occurrences in the sample, without reducing the number of categories. However, any categories with IDs larger than the maximum ID with no occurrences in the sample will not be counted. Example: in sample {1, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 7, 7, 7, 7, 8, 8, 8} the number of categories is reported as 8. Category IDs 2 and 6, which have zero occurrences, are still counted; but if there is a category with ID${}=9$ and zero occurrences, it is not counted.

Mode (output row 16): The most frequently occurring category value. If several values share the greatest frequency of occurrence, then each of them is a mode; but here we report only the smallest of these modes. Example: in sample {1, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 7, 7, 7, 7, 8, 8, 8} the modes are 3 and 7, with 3 reported.

Computed by counting the number of occurrences for each category, then taking the smallest category ID that has the maximum count. Note that the sample modes may be different from the distribution modes, i.e. the categories whose (hypothesized) underlying probability is the maximum over all categories.

Number of modes (output row 17): The number of category values that each have the largest frequency count in the sample. Example: in sample {1, 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, 7, 7, 7, 7, 8, 8, 8} there are two category IDs (3 and 7) that occur the maximum count of 4 times; hence, we return 2.

Computed by counting the number of occurrences for each category, then counting how many categories have the maximum count. Note that the sample modes may be different from the distribution modes, i.e. the categories whose (hypothesized) underlying probability is the maximum over all categories.

Univariate Statistics Returns

The output matrix containing all computed statistics is of size

$17$ rows and as many columns as in the input matrix X. Each row

corresponds to a particular statistic, according to the convention

specified in Table 1. The first $14$ statistics are

applicable for scale columns, and the last $3$ statistics are

applicable for categorical, i.e. nominal and ordinal, columns.

Bivariate Statistics

Description

Bivariate statistics are used to quantitatively describe the association

between two features, such as test their statistical (in-)dependence or

measure the accuracy of one data feature predicting the other feature,

in a sample. The bivar-stats.dml script computes common

bivariate statistics, such as Pearson’s correlation

coefficient and Pearson’s $\chi^2$, in parallel for

many pairs of data features. For a given dataset matrix, script

bivar-stats.dml computes certain bivariate statistics for

the given feature (column) pairs in the matrix. The feature types govern

the exact set of statistics computed for that pair. For example,

Pearson’s correlation coefficient can only be computed on

two quantitative (scale) features like ‘Height’ and ‘Temperature’. It

does not make sense to compute the linear correlation of two categorical

attributes like ‘Hair Color’.

Table 2

The output matrices of bivar-stats.dml have one row per one bivariate

statistic and one column per one pair of input features. This table lists

the meaning of each matrix and each row.

| Output File / Matrix | Row | Name of Statistic |

|---|---|---|

| All Files | 1 | 1-st feature column |

| ” | 2 | 2-nd feature column |

| bivar.scale.scale.stats | 3 | Pearson’s correlation coefficient |

| bivar.nominal.nominal.stats | 3 | Pearson’s $\chi^2$ |

| ” | 4 | Degrees of freedom |

| ” | 5 | $P\textrm{-}$value of Pearson’s $\chi^2$ |

| ” | 6 | Cramér’s $V$ |

| bivar.nominal.scale.stats | 3 | Eta statistic |

| ” | 4 | $F$ statistic |

| bivar.ordinal.ordinal.stats | 3 | Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient |

Bivariate Statistics Details

Script bivar-stats.dml takes an input matrix X whose

columns represent the features and whose rows represent the records of a

data sample. Given X, the script computes certain relevant bivariate

statistics for specified pairs of feature columns X[,i] and

X[,j]. Command-line parameters index1 and index2 specify the

files with column pairs of interest to the user. Namely, the file given

by index1 contains the vector of the 1st-attribute column indices and

the file given by index2 has the vector of the 2nd-attribute column

indices, with “1st” and “2nd” referring to their places in bivariate

statistics. Note that both index1 and index2 files should contain a

1-row matrix of positive integers.

The bivariate statistics to be computed depend on the types, or

measurement levels, of the two columns. The types for each pair are

provided in the files whose locations are specified by types1 and

types2 command-line parameters. These files are also 1-row matrices,

i.e. vectors, that list the 1st-attribute and the 2nd-attribute column

types in the same order as their indices in the index1 and index2

files. The types must be provided as per the following convention:

1 = scale, 2 = nominal, 3 = ordinal.

The script organizes its results into (potentially) four output matrices, one per each type combination. The types of bivariate statistics are defined using the types of the columns that were used for their arguments, with “ordinal” sometimes retrogressing to “nominal.” Table 2 describes what each column in each output matrix contains. In particular, the script includes the following statistics:

- For a pair of scale (quantitative) columns, Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

- For a pair of nominal columns (with finite-sized, fixed, unordered domains), the Pearson’s $\chi^2$ and its p-value.

- For a pair of one scale column and one nominal column, $F$ statistic.

- For a pair of ordinal columns (ordered domains depicting ranks), Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Note that, as shown in Table 2, the output matrices contain the column indices of the features involved in each statistic. Moreover, if the output matrix does not contain a value in a certain cell then it should be interpreted as a $0$ (sparse matrix representation).

Below we list all bivariate statistics computed by script

bivar-stats.dml. The statistics are collected into

several groups by the type of their input features. We refer to the two

input features as $v_1$ and $v_2$ unless specified otherwise; the value

pairs are $(v_{1,i}, v_{2,i})$ for $i=1,\ldots,n$, where $n$ is the

number of rows in X, i.e. the sample size.

Scale-vs-Scale Statistics

Sample statistics that describe association between two quantitative (scale) features. A scale feature has numerical values, with the natural ordering relation.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient: A measure of linear dependence between two numerical features:

\[r = \frac{Cov(v_1, v_2)}{\sqrt{Var v_1 Var v_2}} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n (v_{1,i} - \bar{v}_1) (v_{2,i} - \bar{v}_2)}{\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n (v_{1,i} - \bar{v}_1)^{2\mathstrut} \cdot \sum_{i=1}^n (v_{2,i} - \bar{v}_2)^{2\mathstrut}}}\]Commonly denoted by $r$, correlation ranges between $-1$ and $+1$, reaching ${\pm}1$ when all value pairs $(v_{1,i}, v_{2,i})$ lie on the same line. Correlation near 0 means that a line is not a good way to represent the dependence between the two features; however, this does not imply independence. The sign indicates direction of the linear association: $r > 0$ ($r < 0$) if one feature tends to linearly increase (decrease) when the other feature increases. Nonlinear association, if present, may disobey this sign. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is symmetric: $r(v_1, v_2) = r(v_2, v_1)$; it does not change if we transform $v_1$ and $v_2$ to $a + b v_1$ and $c + d v_2$ where $a, b, c, d$ are constants and $b, d > 0$.

Suppose that we use simple linear regression to represent one feature given the other, say represent $v_{2,i} \approx \alpha + \beta v_{1,i}$ by selecting $\alpha$ and $\beta$ to minimize the least-squares error $\sum_{i=1}^n (v_{2,i} - \alpha - \beta v_{1,i})^2$. Then the best error equals

\[\min_{\alpha, \beta} \,\,\sum_{i=1}^n \big(v_{2,i} - \alpha - \beta v_{1,i}\big)^2 \,\,=\,\, (1 - r^2) \,\sum_{i=1}^n \big(v_{2,i} - \bar{v}_2\big)^2\]In other words, $1\,{-}\,r^2$ is the ratio of the residual sum of squares to the total sum of squares. Hence, $r^2$ is an accuracy measure of the linear regression.

Nominal-vs-Nominal Statistics

Sample statistics that describe association between two nominal categorical features. Both features’ value domains are encoded with positive integers in arbitrary order: nominal features do not order their value domains.

Pearson’s $\chi^2$: A measure of how much the frequencies of value pairs of two categorical features deviate from statistical independence. Under independence, the probability of every value pair must equal the product of probabilities of each value in the pair: $Prob[a, b] - Prob[a]Prob[b] = 0$. But we do not know these (hypothesized) probabilities; we only know the sample frequency counts. Let $n_{a,b}$ be the frequency count of pair $(a, b)$, let $n_a$ and $n_b$ be the frequency counts of $a$ alone and of $b$ alone. Under independence, difference $n_{a,b}{/}n - (n_a{/}n)(n_b{/}n)$ is unlikely to be exactly 0 due to sample randomness, yet it is unlikely to be too far from 0. For some pairs $(a,b)$ it may deviate from 0 farther than for other pairs. Pearson’s $\chi^2$ is an aggregate measure that combines squares of these differences across all value pairs:

\[\chi^2 \,\,=\,\, \sum_{a,\,b} \Big(\frac{n_a n_b}{n}\Big)^{-1} \Big(n_{a,b} - \frac{n_a n_b}{n}\Big)^2 \,=\,\, \sum_{a,\,b} \frac{(O_{a,b} - E_{a,b})^2}{E_{a,b}}\]where $O_{a,b} = n_{a,b}$ are the observed frequencies and $E_{a,b} = (n_a n_b){/}n$ are the expected frequencies for all pairs $(a,b)$. Under independence (plus other standard assumptions) the sample $\chi^2$ closely follows a well-known distribution, making it a basis for statistical tests for independence, see $P\textrm{-}$value of Pearson’s $\chi^2$ for details. Note that Pearson’s $\chi^2$ does not measure the strength of dependence: even very weak dependence may result in a significant deviation from independence if the counts are large enough. Use Cramér’s $V$ instead to measure the strength of dependence.

Degrees of freedom: An integer parameter required for the interpretation of Pearson’s $\chi^2$ measure. Under independence (plus other standard assumptions) the sample $\chi^2$ statistic is approximately distributed as the sum of $d$ squares of independent normal random variables with mean 0 and variance 1, where $d$ is this integer parameter. For a pair of categorical features such that the $1^{\textrm{st}}$ feature has $k_1$ categories and the $2^{\textrm{nd}}$ feature has $k_2$ categories, the number of degrees of freedom is $d = (k_1 - 1)(k_2 - 1)$.

$P\textrm{-}$value of Pearson’s $\chi^2$: A measure of how likely we would observe the current frequencies of value pairs of two categorical features assuming their statistical independence. More precisely, it computes the probability that the sum of $d$ squares of independent normal random variables with mean 0 and variance 1 (called the $\chi^2$ distribution with $d$ degrees of freedom) generates a value at least as large as the current sample Pearson’s $\chi^2$. The $d$ parameter is degrees of freedom, see above. Under independence (plus other standard assumptions) the sample Pearson’s $\chi^2$ closely follows the $\chi^2$ distribution and is unlikely to land very far into its tail. On the other hand, if the two features are dependent, their sample Pearson’s $\chi^2$ becomes arbitrarily large as $n\to\infty$ and lands extremely far into the tail of the $\chi^2$ distribution given a large enough data sample. $P\textrm{-}$value of Pearson’s $\chi^2$ returns the tail “weight” on the right-hand side of Pearson’s $\chi^2$:

\[P = Prob\big[r \geq \textrm{Pearson’s $\chi^2$} \big|\,\, r \sim \textrm{the $\chi^2$ distribution}\big]\]As any probability, $P$ ranges between 0 and 1. If $P\leq 0.05$, the dependence between the two features may be considered statistically significant (i.e. their independence is considered statistically ruled out). For highly dependent features, it is not unusual to have $P\leq 10^{-20}$ or less, in which case our script will simply return $P = 0$. Independent features should have their $P\geq 0.05$ in about 95% cases.

Cramér’s $V$: A measure for the strength of association, i.e. of statistical dependence, between two categorical features, conceptually similar to Pearson’s correlation coefficient. It divides the observed Pearson’s $\chi^2$ by the maximum possible $\chi^2_{\textrm{max}}$ given $n$ and the number $k_1, k_2$ of categories in each feature, then takes the square root. Thus, Cramér’s $V$ ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 implies no association and 1 implies the maximum possible association (one-to-one correspondence) between the two features. See Pearson’s $\chi^2$ for the computation of $\chi^2$; its maximum = $n\cdot\min\{k_1\,{-}\,1, k_2\,{-}\,1\}$ where the $1^{\textrm{st}}$ feature has $k_1$ categories and the $2^{\textrm{nd}}$ feature has $k_2$ categories [AcockStavig1979], so

\[\textrm{Cramér’s $V$} \,\,=\,\, \sqrt{\frac{\textrm{Pearson’s $\chi^2$}}{n\cdot\min\{k_1\,{-}\,1, k_2\,{-}\,1\}}}\]As opposed to $P\textrm{-}$value of Pearson’s $\chi^2$, which goes to 0 (rapidly) as the features’ dependence increases, Cramér’s $V$ goes towards 1 (slowly) as the dependence increases. Both Pearson’s $\chi^2$ and $P\textrm{-}$value of Pearson’s $\chi^2$ are very sensitive to $n$, but in Cramér’s $V$ this is mitigated by taking the ratio.

Nominal-vs-Scale Statistics

Sample statistics that describe association between a categorical feature (order ignored) and a quantitative (scale) feature. The values of the categorical feature must be coded as positive integers.

Eta statistic: A measure for the strength of association (statistical dependence) between a nominal feature and a scale feature, conceptually similar to Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Ranges from 0 to 1, approaching 0 when there is no association and approaching 1 when there is a strong association. The nominal feature, treated as the independent variable, is assumed to have relatively few possible values, all with large frequency counts. The scale feature is treated as the dependent variable. Denoting the nominal feature by $x$ and the scale feature by $y$, we have:

\[\eta^2 \,=\, 1 - \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \big(y_i - \hat{y}[x_i]\big)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \bar{y})^2}, \,\,\,\,\textrm{where}\,\,\,\, \hat{y}[x] = \frac{1}{\mathop{\mathrm{freq}}(x)}\sum_{i=1}^n \,\left\{\!\!\begin{array}{rl} y_i & \textrm{if $x_i = x$}\\ 0 & \textrm{otherwise}\end{array}\right.\!\!\!\]and $\bar{y} = (1{/}n)\sum_{i=1}^n y_i$ is the mean. Value $\hat{y}[x]$ is the average of $y_i$ among all records where $x_i = x$; it can also be viewed as the “predictor” of $y$ given $x$. Then $\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}[x_i])^2$ is the residual error sum-of-squares and $\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \bar{y})^2$ is the total sum-of-squares for $y$. Hence, $\eta^2$ measures the accuracy of predicting $y$ with $x$, just like the “R-squared” statistic measures the accuracy of linear regression. Our output $\eta$ is the square root of $\eta^2$.

$F$ statistic: A measure of how much the values of the scale feature, denoted here by $y$, deviate from statistical independence on the nominal feature, denoted by $x$. The same measure appears in the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Like Pearson’s $\chi^2$, $F$ statistic is used to test the hypothesis that $y$ is independent from $x$, given the following assumptions:

- The scale feature $y$ has approximately normal distribution whose mean may depend only on $x$ and variance is the same for all $x$.

- The nominal feature $x$ has relatively small value domain with large frequency counts, the $x_i$-values are treated as fixed (non-random).

- All records are sampled independently of each other.

To compute $F$ statistic, we first compute $\hat{y}[x]$ as the average of $y_i$ among all records where $x_i = x$. These $\hat{y}[x]$ can be viewed as “predictors” of $y$ given $x$; if $y$ is independent on $x$, they should “predict” only the global mean $\bar{y}$. Then we form two sums-of-squares:

- Residual sum-of-squares of the “predictor” accuracy: $y_i - \hat{y}[x_i]$.

- Explained sum-of-squares of the “predictor” variability: $\hat{y}[x_i] - \bar{y}$.

$F$ statistic is the ratio of the explained sum-of-squares to the residual sum-of-squares, each divided by their corresponding degrees of freedom:

\[F \,\,=\,\, \frac{\sum_{x}\, \mathop{\mathrm{freq}}(x) \, \big(\hat{y}[x] - \bar{y}\big)^2 \,\big/\,\, (k\,{-}\,1)}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \big(y_i - \hat{y}[x_i]\big)^2 \,\big/\,\, (n\,{-}\,k)} \,\,=\,\, \frac{n\,{-}\,k}{k\,{-}\,1} \cdot \frac{\eta^2}{1 - \eta^2}\]Here $k$ is the domain size of the nominal feature $x$. The $k$ “predictors” lose 1 freedom due to their linear dependence with $\bar{y}$; similarly, the $n$ $y_i$-s lose $k$ freedoms due to the “predictors”.

The statistic can test if the independence hypothesis of $y$ from $x$ is reasonable; more generally (with relaxed normality assumptions) it can test the hypothesis that the mean of $y$ among records with a given $x$ is the same for all $x$. Under this hypothesis $F$ statistic has, or approximates, the $F(k\,{-}\,1, n\,{-}\,k)$-distribution. But if the mean of $y$ given $x$ depends on $x$, $F$ statistic becomes arbitrarily large as $n\to\infty$ (with $k$ fixed) and lands extremely far into the tail of the $F(k\,{-}\,1, n\,{-}\,k)$-distribution given a large enough data sample.

Ordinal-vs-Ordinal Statistics

Sample statistics that describe association between two ordinal categorical features. Both features’ value domains are encoded with positive integers, so that the natural order of the integers coincides with the order in each value domain.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient: A measure for the strength of association (statistical dependence) between two ordinal features, conceptually similar to Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Specifically, it is Pearson’s correlation coefficient applied to the feature vectors in which all values are replaced by their ranks, i.e. their positions if the vector is sorted. The ranks of identical (duplicate) values are replaced with their average rank. For example, in vector $(15, 11, 26, 15, 8)$ the value “15” occurs twice with ranks 3 and 4 per the sorted order $(8_1, 11_2, 15_3, 15_4, 26_5)$; so, both values are assigned their average rank of $3.5 = (3\,{+}\,4)\,{/}\,2$ and the vector is replaced by $(3.5,\, 2,\, 5,\, 3.5,\, 1)$.

Our implementation of Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is geared towards features having small value domains and large counts for the values. Given the two input vectors, we form a contingency table $T$ of pairwise frequency counts, as well as a vector of frequency counts for each feature: $f_1$ and $f_2$. Here in $T_{i,j}$, $f_{1,i}$, $f_{2,j}$ indices $i$ and $j$ refer to the order-preserving integer encoding of the feature values. We use prefix sums over $f_1$ and $f_2$ to compute the values’ average ranks: $r_{1,i} = \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} f_{1,j} + (f_{1,i}\,{+}\,1){/}2$, and analogously for $r_2$. Finally, we compute rank variances for $r_1, r_2$ weighted by counts $f_1, f_2$ and their covariance weighted by $T$, before applying the standard formula for Pearson’s correlation coefficient:

\[\rho \,\,=\,\, \frac{Cov_T(r_1, r_2)}{\sqrt{Var_{f_1}(r_1)Var_{f_2}(r_2)}} \,\,=\,\, \frac{\sum_{i,j} T_{i,j} (r_{1,i} - \bar{r}_1) (r_{2,j} - \bar{r}_2)}{\sqrt{\sum_i f_{1,i} (r_{1,i} - \bar{r}_1)^{2\mathstrut} \cdot \sum_j f_{2,j} (r_{2,j} - \bar{r}_2)^{2\mathstrut}}}\]where $\bar{r_1} = \sum_i r_{1,i} f_{1,i}{/}n$, analogously for $\bar{r}_2$. The value of $\rho$ lies between $-1$ and $+1$, with sign indicating the prevalent direction of the association: $\rho > 0$ ($\rho < 0$) means that one feature tends to increase (decrease) when the other feature increases. The correlation becomes 1 when the two features are monotonically related.

Bivariate Statistics Returns

A collection of (potentially) 4 matrices. Each matrix contains bivariate statistics that resulted from a different combination of feature types. There is one matrix for scale-scale statistics (which includes Pearson’s correlation coefficient), one for nominal-nominal statistics (includes Pearson’s $\chi^2$), one for nominal-scale statistics (includes $F$ statistic) and one for ordinal-ordinal statistics (includes Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient). If any of these matrices is not produced, then no pair of columns required the corresponding type combination. See Table 2 for the matrix naming and format details.

Stratified Bivariate Statistics

Stratified Bivariate Statistics Description

The stratstats.dml script computes common bivariate

statistics, such as correlation, slope, and their p-value, in parallel

for many pairs of input variables in the presence of a confounding

categorical variable. The values of this confounding variable group the

records into strata (subpopulations), in which all bivariate pairs are

assumed free of confounding. The script uses the same data model as in

one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with strata representing

population samples. It also outputs univariate stratified and bivariate

unstratified statistics.

To see how data stratification mitigates confounding, consider an (artificial) example in Table 3. A highly seasonal retail item was marketed with and without a promotion over the final 3 months of the year. In each month the sale was more likely with the promotion than without it. But during the peak holiday season, when shoppers came in greater numbers and bought the item more often, the promotion was less frequently used. As a result, if the 4-th quarter data is pooled together, the promotion’s effect becomes reversed and magnified. Stratifying by month restores the positive correlation.

The script computes its statistics in parallel over all possible pairs from two specified sets of covariates. The 1-st covariate is a column in input matrix $X$ and the 2-nd covariate is a column in input matrix $Y$; matrices $X$ and $Y$ may be the same or different. The columns of interest are given by their index numbers in special matrices. The stratum column, specified in its own matrix, is the same for all covariate pairs.

Both covariates in each pair must be numerical, with the 2-nd covariate normally distributed given the 1-st covariate (see Details). Missing covariate values or strata are represented by “NaN”. Records with NaN’s are selectively omitted wherever their NaN’s are material to the output statistic.

Table 3

Stratification example: the effect of the promotion on average sales becomes reversed and amplified (from $+0.1$ to $-0.5$) if we ignore the months.

| Month | Oct | Nov | Dec | Oct | -Dec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customers (millions) | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 |

| Promotions (0 or 1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Avg sales per 1000 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

Table 4

The stratstats.dml output matrix has one row per each distinct pair of

1-st and 2-nd covariates, and 40 columns with the statistics described here.

| Col | Meaning | Col | Meaning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | $X$-column number | 11 | $Y$-column number | ||

| 02 | presence count for $x$ | 12 | presence count for $y$ | ||

| 03 | global mean $(x)$ | 13 | global mean $(y)$ | ||

| 04 | global std. dev. $(x)$ | 14 | global std. dev. $(y)$ | ||

| 1-st covariate | 05 | stratified std. dev. $(x)$ | 2-nd covariate | 15 | stratified std. dev. $(y)$ |

| 06 | $R^2$ for $x \sim $ strata | 16 | $R^2$ for $y \sim $ strata | ||

| 07 | adjusted $R^2$ for $x \sim $ strata | 17 | adjusted $R^2$ for $y \sim $ strata | ||

| 08 | p-value, $x \sim $ strata | 18 | p-value, $y \sim $ strata | ||

| 09 - 10 | reserved | 19 - 20 | reserved | ||

| 21 | presence count $(x, y)$ | 31 | presence count $(x, y, s)$ | ||

| 22 | regression slope | 32 | regression slope | ||

| 23 | regres. slope std. dev. | 33 | regres. slope std. dev. | ||

| 24 | correlation $= \pm\sqrt{R^2}$ | 34 | correlation $= \pm\sqrt{R^2}$ | ||

| $y \sim x$, NO strata | 25 | residual std. dev. | $y \sim x$ AND strata | 35 | residual std. dev. |

| 26 | $R^2$ in $y$ due to $x$ | 36 | $R^2$ in $y$ due to $x$ | ||

| 27 | adjusted $R^2$ in $y$ due to $x$ | 37 | adjusted $R^2$ in $y$ due to $x$ | ||

| 28 | p-value for “slope = 0” | 38 | p-value for “slope = 0” | ||

| 29 | reserved | 39 | # strata with ${\geq}\,2$ count | ||

| 30 | reserved | 40 | reserved |

Stratified Bivariate Statistics Details

Suppose we have $n$ records of format $(i, x, y)$, where $i\in{1,\ldots, k}$ is a stratum number and $(x, y)$ are two numerical covariates. We want to analyze conditional linear relationship between $y$ and $x$ conditioned by $i$. Note that $x$, but not $y$, may represent a categorical variable if we assign a numerical value to each category, for example 0 and 1 for two categories.

We assume a linear regression model for $y$:

\[\begin{equation} y_{i,j} \,=\, \alpha_i + \beta x_{i,j} + {\varepsilon}_{i,j}\,, \quad\textrm{where}\,\,\,\, {\varepsilon}_{i,j} \sim Normal(0, \sigma^2) \end{equation}\]Here $i = 1\ldots k$ is a stratum number and $j = 1\ldots n_i$ is a record number in stratum $i$; by $n_i$ we denote the number of records available in stratum $i$. The noise term $\varepsilon_{i,j}$ is assumed to have the same variance in all strata. When $n_i\,{>}\,0$, we can estimate the means of $x_{i, j}$ and $y_{i, j}$ in stratum $i$ as

\[\bar{x}_i \,= \Big(\sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{n_i} \,x_{i, j}\Big) / n_i\,;\quad \bar{y}_i \,= \Big(\sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{n_i} \,y_{i, j}\Big) / n_i\]If $\beta$ is known, the best estimate for $\alpha_i$ is $\bar{y}_i - \beta \bar{x}_i$, which gives the prediction error sum-of-squares of

\[\begin{equation} \sum\nolimits_{i=1}^k \sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{n_i} \big(y_{i,j} - \beta x_{i,j} - (\bar{y}_i - \beta \bar{x}_i)\big)^2 \,\,=\,\, \beta^{2\,}V_x \,-\, 2\beta \,V_{x,y} \,+\, V_y \label{eqn:stratsumsq} \end{equation}\]where $V_x$, $V_y$, and $V_{x, y}$ are, correspondingly, the “stratified” sample estimates of variance $Var(x)$ and $Var(y)$ and covariance $Cov(x,y)$ computed as

\[\begin{aligned} V_x \,&=\, \sum\nolimits_{i=1}^k \sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{n_i} \big(x_{i,j} - \bar{x}_i\big)^2; \quad V_y \,=\, \sum\nolimits_{i=1}^k \sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{n_i} \big(y_{i,j} - \bar{y}_i\big)^2;\\ V_{x,y} \,&=\, \sum\nolimits_{i=1}^k \sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{n_i} \big(x_{i,j} - \bar{x}_i\big)\big(y_{i,j} - \bar{y}_i\big) \end{aligned}\]They are stratified because we compute the sample (co-)variances in each stratum $i$ separately, then combine by summation. The stratified estimates for $Var(X)$ and $Var(Y)$ tend to be smaller than the non-stratified ones (with the global mean instead of $\bar{x_i}$ and $\bar{y_i}$) since $\bar{x_i}$ and $\bar{y_i}$ fit closer to $x_{i,j}$ and $y_{i,j}$ than the global means. The stratified variance estimates the uncertainty in $x_{i,j}$ and $y_{i,j}$ given their stratum $i$.

Minimizing over $\beta$ the error sum-of-squares (2) gives us the regression slope estimate $\hat{\beta} = V_{x,y} / V_x$, with (2) becoming the residual sum-of-squares (RSS):

\[\mathrm{RSS} \,\,=\, \, \sum\nolimits_{i=1}^k \sum\nolimits_{j=1}^{n_i} \big(y_{i,j} - \hat{\beta} x_{i,j} - (\bar{y}_i - \hat{\beta} \bar{x}_i)\big)^2 \,\,=\,\, V_y \,\big(1 \,-\, V_{x,y}^2 / (V_x V_y)\big)\]The quantity $\hat{R}^2 = V_{x,y}^2 / (V_x V_y)$, called $R$-squared, estimates the fraction of stratified variance in $y_{i,j}$ explained by covariate $x_{i, j}$ in the linear regression model (1). We define stratified correlation as the square root of $\hat{R}^2$ taken with the sign of $V_{x,y}$. We also use RSS to estimate the residual standard deviation $\sigma$ in (1) that models the prediction error of $y_{i,j}$ given $x_{i,j}$ and the stratum:

\[\hat{\beta}\, =\, \frac{V_{x,y}}{V_x}; \,\,\,\, \hat{R} \,=\, \frac{V_{x,y}}{\sqrt{V_x V_y}}; \,\,\,\, \hat{R}^2 \,=\, \frac{V_{x,y}^2}{V_x V_y}; \,\,\,\, \hat{\sigma} \,=\, \sqrt{\frac{\mathrm{RSS}}{n - k - 1}}\,\,\,\, \Big(n = \sum_{i=1}^k n_i\Big)\]The $t$-test and the $F$-test for the null-hypothesis of “$\beta = 0$” are obtained by considering the effect of $\hat{\beta}$ on the residual sum-of-squares, measured by the decrease from $V_y$ to RSS. The $F$-statistic is the ratio of the “explained” sum-of-squares to the residual sum-of-squares, divided by their corresponding degrees of freedom. There are $n\,{-}\,k$ degrees of freedom for $V_y$, parameter $\beta$ reduces that to $n\,{-}\,k\,{-}\,1$ for RSS, and their difference $V_y - {}$RSS has just 1 degree of freedom:

\[F \,=\, \frac{(V_y - \mathrm{RSS})/1}{\mathrm{RSS}/(n\,{-}\,k\,{-}\,1)} \,=\, \frac{\hat{R}^2\,(n\,{-}\,k\,{-}\,1)}{1-\hat{R}^2}; \quad t \,=\, \hat{R}\, \sqrt{\frac{n\,{-}\,k\,{-}\,1}{1-\hat{R}^2}}.\]The $t$-statistic is simply the square root of the $F$-statistic with the appropriate choice of sign. If the null hypothesis and the linear model are both true, the $t$-statistic has Student $t$-distribution with $n\,{-}\,k\,{-}\,1$ degrees of freedom. We can also compute it if we divide $\hat{\beta}$ by its estimated standard deviation:

\[st.dev(\hat{\beta})_{\mathrm{est}} \,=\, \hat{\sigma}\,/\sqrt{V_x} \quad\Longrightarrow\quad t \,=\, \hat{R}\sqrt{V_y} \,/\, \hat{\sigma} \,=\, \beta \,/\, st.dev(\hat{\beta})_{\mathrm{est}}\]The standard deviation estimate for $\beta$ is included in

stratstats.dml output.

Returns

The output matrix format is defined in Table 4.